Our colleague and researcher Bryan Tan has published a research note for future South Korean administrations. His note looks at South Korea’s economic initiatives vis-a-vis North Korea, and suggest areas where capacity building can be pursued to support peaceful economic integration. For the full paper, please email media@chosonexchange.org. A draft truncated public version prepared for the World Economic Forum’s Global Future Council is attached here.

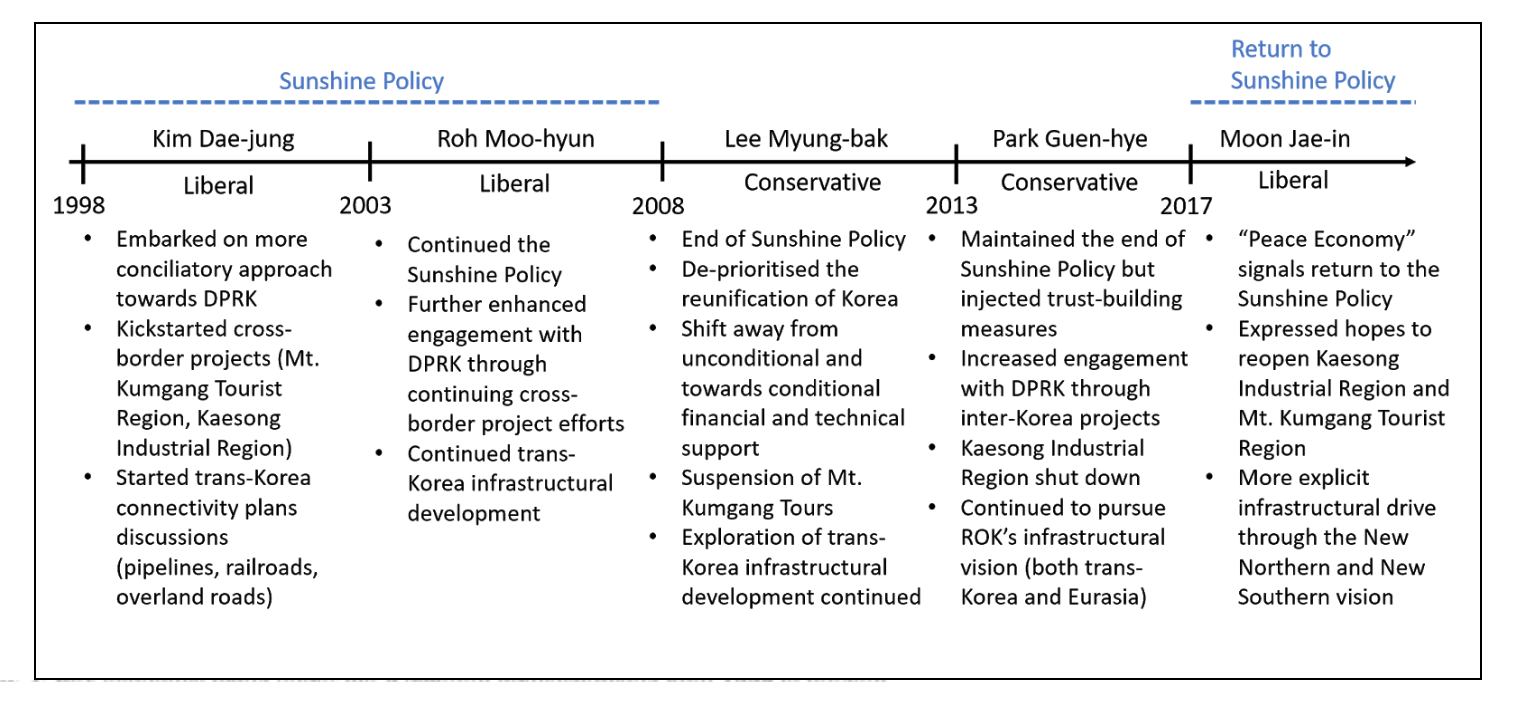

Fig 1: Economic interactions between both Koreas over successive South Korean administrations

This paper summarises the general economic posturing of South Korea (ROK) towards the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) under the last five presidents – Kim Dae-jung (1998 – 2003), Roh Moo-hyun (2003 – 2008), Lee Myung-bak (2008 – 2013), Park Geun-hye (2013 – 2017) and Moon Jae-in (2017 – present). This paper identifies both changes and continuations of key economic policies across these five administrations, and sheds light on how present and future ROK administrations could position their economic plans towards DPRK. Consistent policy themes across the decades also suggests areas in which institutions can step in to provide relevant capacity building programmes.

As seen in Fig. 1, whether ROK pursues a more conciliatory or a more hard-line policy towards DPRK depends on the political leaning of the government of the day. However, two key policies run consistent across all five administrations:

1. Desire for Eventual Re-unification of the Korean Peninsula

The eventual re-unification of the two Koreas into a single sovereign state is a national consensus that is unlikely to change in the years ahead. The process towards reunification was started by the June 15th North-South Joint Declaration in June 2000 and was reaffirmed by the Panmunjom Declaration for Peace, Prosperity and Unification of the Korean Peninsula in April 2018.

2. ROK’s Infrastructural Vision

On one hand, the erratic DPRK necessitates ROK to maintain a close USA-ROK military alliance. On the other hand, geographic proximity and the large Chinese market means that ROK’s trade is deeply tied with China. The rise of China places ROK in a strategic dilemma as it seeks to precariously balance its relations between USA, its key security ally, and China, its top trading partner. As the ROK’s economy leans too heavily on both the USA and China, there is an impetus for the ROK to search for new markets and new growth engines in Northeast Asia. The longstanding infrastructural vision of the ROK seeks to do so, by further diversifying its economy through enhancing trade with both its northern and southern neighbours, as well as by driving new economic growth poles in the region.

In addition, as the world’s third largest importer of Liquified Natural Gas (LNG), ROK hopes to increase access to cheaper energy and diversify its import source. Owing to the unique geography of the Korean peninsula and its vicinity, the most cost-effective way to construct the relevant infrastructure (e.g. gas pipelines, railroads) would be to cut through the DPRK to reach ROK. As such, the success of trans-Korean infrastructural projects is highly dependent on the North-South political climate and are usually pitched as economic gains for the DPRK whilst steps towards reunification are taken.

Over the decades, the increased focus and more explicitly mentioned infrastructural vision of ROK reflect the sense of urgency it faces in striking a delicate balance between USA and China. Furthermore, the slowing ROK economy and worsening global economic conditions also place greater pressure on ROK to seek more jobs, enhanced trade and cheaper energy through these infrastructural projects.